What You'll Learn

Social determinants of health (SDoH) have reframed how we view, discuss, and solve health disparities. Here’s why it matters to your members.

- What Are Social Determinants of Health?

- The Relationship Between Health Equity & SDoH

- The Distinction Between SDoH & Health-Related Social Needs

- Member Stories: The Impact of Addressing Unmet Social Needs

- Components of a Community-Based Approach to Overcome SDoH Barriers

- Solving the Last Mile for Social Determinants

- Reema’s SDoH Resource Library

What Shapes Our Health?

As children, we never see health as anything but personal: we got sick, we went to the doctor, we got better (hopefully). And health risk factors were nearby—germs from siblings or school friends, injuries at parks or in sports, etc. The world of health was narrow. Of course, it’s more complicated than that: individual wellbeing can be understood not just by a range of personal experiences but through the broad contextual factors that shape our lives. These political, economic, and geographic forces have come to be known as the Social Determinants of Health (SDoH).

Contextualizing health needs through SDoH allows us to identify more effective and farther reaching solutions. Solutions that impact entire communities, not just individuals. But how do we do that? We do it by starting with community-based interventions that recognize how SDoH affects individual lives.

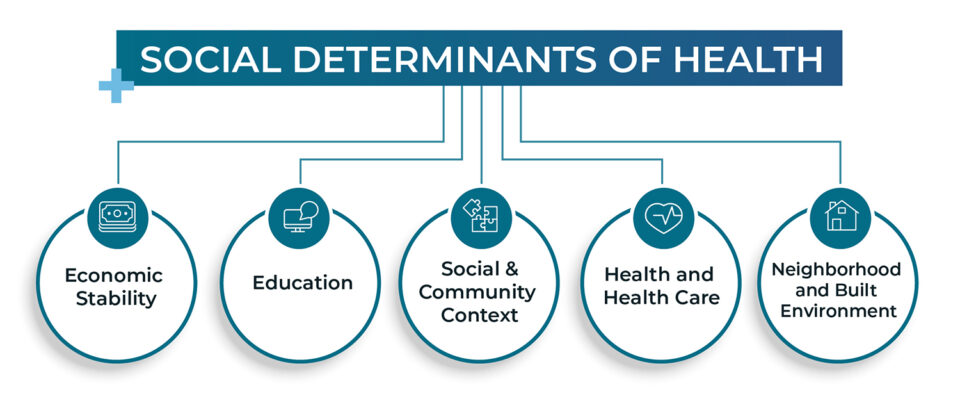

What are Social Determinants of Health?

It’s often said that a person’s ZIP code is a better predictor of a person’s health than their genetics or personal decisions. This shorthand reflects the five key areas that capture how where we live affects how well we live:

- Economic Stability

- Education

- Social and Community Context

- Health and Health Care

- Neighborhood and Built Environment

Social Determinants of Health are Neutral

SDoH are most often presented as inherently negative—as something to be “addressed.” They’re also often associated with lower income populations, but everyone’s lives are shaped by social determinants of health, no matter their socio-economic status.

It’s more helpful to view SDoH as a neutral lens for evaluating how a person’s health is shaped, for better or worse, by forces larger than their personal choices. For example, a person’s level of housing security indicates their level of economic stability. If a person and those around them are housed securely, their well-being is likely greater than a person whose housing is less secure.

Similarly, a person’s level of education (and the broader community’s access to education) predicts their level of health. Food and educational access determine a population’s health status in general; they don’t necessarily determine it negatively. Communities with high levels of access to food and education do not need to have their SDoH “addressed.” In short, SDoH tells us where to look, not what we will see.

Why SDoH? The Health Equity Question

In addition to improving individual and population health, addressing the social risk factors associated with the SDoH that adversely affect people can improve health equity. Health equity means “that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible,” and it’s the larger ethical principle that guides and motivates people to address SDoH. When we improve health equity, we implement policies that eliminate barriers and obstacles to health and reduce disparities in the health of marginalized or excluded groups. Creating health equity is the ultimate goal. Addressing SDoH is a means to that goal.

Social Determinants of Health Need Policy Solutions

However, leaning too heavily on the language of SDoH poses a risk: when we employ SDoH as a lens to evaluate population health, then our solutions must be enacted at the level. For example, a policy intervention that seeks to alleviate insecure housing by allowing Medicaid to cover rent can significantly improve health outcomes for a whole community. This is what it would mean to truly address SDoH. But because these interventions require significant political capital and access to the levers of power, most of us working in this space are not targeting these sorts of solutions.

Targeting Social Risk Factors and Health-Related Social Needs

If we’re not pursuing policy change, and if we’re not “addressing SDoH”, then what are we doing? How do we discuss the negative conditions associated with poorer health that we seek to address when we address SDoH? We need a different term. That term is social risk factors. Social risk factors are those aspects of SDoH that negatively impact health: low education, insecure housing or food, lack of transportation, etc.

But the term social risk factors isn’t the whole story either. A member may have a number of social risk factors but not experience them as actual health-related social needs. To successfully help members, we can’t simply talk about SDoH or assume everyone is affected by their social risk factors. Instead it means we must assess how the their social needs impact their health, while at the same time recognizing their social risk factors and their community context.

Where to Intervene? Upstream or Downstream?

SDoH, social risk factors, and health-related social needs help indicate where we should expect to intervene: either upstream at the larger political, geographic, and economic forces (i.e., SDoH) or downstream at health-related social needs. Allowing Medicaid to cover rent is an upstream intervention; helping an individual pay their rent (irrespective of any larger policy change) is a downstream intervention. Both interventions are necessary, of course, but the work we and others like us do exist downstream by addressing social risk factors that manifest as health-related social needs.

Addressing SDoH means improving the conditions in which people live in ways that improve health outcomes (building affordable housing, offering better access to education, etc). On the ground it means addressing members in communities with higher social risk factors who are currently experiencing greater health-related social needs.

Health-Related Social Needs vs. Social Determinants of Health: The Words We Use Matters

Advocating for these kinds of definitions may seem pedantic. What difference does it make how we talk about SDoH challenges so long as we’re helping people get the help they need? We believe it makes a big difference. First, it’s simply a more accurate representation of the relationship between concepts too carelessly tossed around. This sensitivity is necessary if we want to earn the trust of those we collaborate with.

Equally important, these distinctions help to clarify how exactly we are to understand the problems we hope to address. Relying on a SDoH framework not only inaccurately describes our work, but it also fails to train our focus on the health-related social needs and social risk factors where our interventions can do the most good.

For example, in order to understand how to help people, it’s common to use either census and claims data or conduct surveys, neither of which are particularly effective. It’s notoriously hard to predict which interventions to pursue using census and claims data alone, and self-reporting on surveys is also unreliable: sometimes people don’t want to share; sometimes they don’t even know what they need.

There’s a more effective way to do this, of course; a way that accurately captures the on-the-ground health-related social needs of a person and the social risk factors of their community. How? We believe the best interventions are those that help people with significant social needs while accounting for social risk factors. And we believe this happens most successfully and most efficiently when we take a community-based approach that recognizes how social needs show up in individual lives.

Calvin's Story

Take Calvin, for example. When we met him, he was living in his van after a recent divorce. His most important social need was to change this and find him a place to live. So one of our Community Guides worked with him to first find temporary and then permanent housing. The Guide accompanied him on apartment tours and, due to his dyslexia, helped him fill out the necessary forms and applications. The process, of course, took a long time and Calvin became discouraged, particularly when he had to give up his van and his health continued to decline.

One year later, his HUD application was finally accepted and he moved into his apartment. His health has improved, he’s less lonely, and he’s more optimistic. Without access to an apartment, Calvin’s health would have continued to deteriorate and he would not have had a stable base from which to tackle the next phase of his life.

Sandra's Story

Identifying social needs can be difficult, however. When asked, it’s common for people to respond, “I don’t need anything.” Responses like this occur when people are accustomed to the challenges in their lives and from their sense that tangible help is not available (i.e. the last mile of SDoH issues).

For example, when we met Sandra, she didn’t tell us that she was being evicted or struggling to quit smoking or had a history with mental illness, all significant social risk factors. Instead, we identified a couple of key phrases from our conversation—about grandchildren and end-of-the-month SNAP benefits—that our system flagged as predictive of food insecurity.

Addressing this social need built trust, and when we brought her food, we learned more about her, her family, and that she needed adult diapers. Adult diapers are a sensitive topic, but delivering them led her to tell us about a pending eviction, challenges to quit smoking, and a history of mental illness. All of which are addressable through existing resources, but none of which she was fully aware of, or had the time or energy to work through herself. Helping to address some of Sandra’s social needs opened the door to understanding her other social risk factors.

Three Powerful Components of a Community-Based Approach

Calvin’s and Sandra’s stories illustrate how adverse SDoH show up in people’s real lives, in often personal and member-specific ways. For them, a one-size-fits-all system won’t work to help individuals overcome their unique barriers. And simply addressing individual social needs, while impactful for each person, risks becoming a bandaid rather than a longer term solution. What’s needed is a community-based approach, one that recognizes how social risk factors show up locally and offers solutions that respect community context.

Community-based healthcare as a concept is not new. But in recent years healthcare organizations have begun focusing on what it means, the value it carries, and how it impacts health outcomes. As more healthcare organizations start to explore how a community-based approach to care works, understanding what it is and the benefits becomes more important than ever.

#1 - Community Based Models Manage Complexity

Taking a community-based approach means providing care for the community, by the community, with the goal of working together to improve health for all to address food insecurity, transportation, housing, manage chronic conditions, reduce social isolation and loneliness, and overcome other non-medical risk factors (among others). Addressing these social risk factors at the community level improves health outcomes and reduces the cost of care.

This is particularly true for “high-need, high-cost” members, those with complex health conditions and social risk factors who often have larger gaps and trouble navigating the healthcare system on their own. This can be for many reasons, but the system itself isn’t straightforward or easy to maneuver and can be incredibly complex to navigate, even for those that understand the system well.

#2 - Meet Members Where They Are

A community-based approach is key to truly person-centered care. Meeting members where they are with the right message, resource, and level of support can be the difference between addressing an unmet need at a critical moment or responding to an emergency health situation. Personalization of course means different things in different scenarios. Sometimes it’s how we choose to communicate with a member and other times it’s driving over to the member’s house to help them with the action they need to take.

A community-based approach makes it possible to know a member on a personal level and make informed decisions based on their health history, preferences, and unique lives. This might mean driving a member to an appointment, helping them pick up groceries, or going with them to find new housing. Standing alongside members and helping them navigate their individual challenges is the ultimate personalized approach.

#3 - Connect with Shared Identity

Critical to the success of a community-based approach is shared identity, meeting members where they are. Because representation through shared identity matters greatly in community-based healthcare, engaging people within their own communities with other members of that community is necessary.

Community-based healthcare thrives when we establish a strong foundation for authentic connections with members. One of the ways this happens is through shared identity. This isn’t just shared demographic characteristics either. It’s about understanding the community in which they live, the resources available, the transportation options, what’s going on with the weather, and so much more. To establish more meaningful relationships, this foundation must come first, and it can’t be achieved remotely. If health is local, then health care must be local too.

There are many benefits of a community-based healthcare approach. We believe that when we do it right, the benefits reverberate way beyond the individual member. Some of the key advantages of a community-based care system include localization, better opportunity to identify barriers, personalization, and impacting outcomes through shared identity.

Social Determinants of Health and the Last Mile Problem

Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) also has a “last mile” problem: The programs built to address health disparities at the population level must still reach that population. As we’ve argued, “reaching that population” can’t simply mean building a program or informing individuals that a program or resource exists. Programs alone don’t close gaps. Neither does knowledge of those programs nor referrals to them. At least not for those requiring the most help.

Take food insecurity, for example. Is this an access problem? A transportation problem? A financial problem? All three? The multifaceted nature of these issues means that SDoH’s last mile is messy. Creating a weekly farmer’s market in a food desert solves the access issue, but not the other two. But integrating different solutions together to address these complex issues also isn’t simple, not only because integrating different programs is challenging, but because it’s not always entirely clear what prevents someone from taking advantage of the opportunities around them in the first place. What’s needed is a more personal approach, one that appreciates the nuances of an individual’s situation.

The Challenge and the Future

Addressing SDoH in the community is an ongoing challenge. After all, while it’s already difficult to identify the unmet social needs for any health plan member, it’s even more difficult to identify them when they aren’t reachable in the first place. Engaging these members—often those with the highest needs – can be a significant barrier to better health and a consistent challenge for even the most innovative health plans. Adopting a community-based approach will produce better results; pairing that approach with a thoughtful technological strategy can ensure success.

By combining advanced technology and comprehensive data models and pairing them with meaningful human connections led by empathy, a community-based approach can engage hard-to-reach members, talk to them on their terms, and motivate them in ways that work. All to create a more balanced approach to better care.

Engaging the Unengaged

For members who are harder to reach, communicating at the right time using the right channel could be the difference between a member getting the care they need at a critical moment or an emergency situation. This is why meeting members where they are is so important and why leveraging digital communication methods, like text messaging, has proven to boost member engagement rates, leading to improved outcomes.

We’ve found that texting is a great and effective way to communicate with members and is often the preferred communication method for many in the population we serve. Using their preferred way to communicate builds trust. This, in turn, builds the kind of relationship that leads to a higher likelihood of continued communication, particularly for members who may not have been previously engaged.

Identifying Unique Needs

Every member is unique, with individual healthcare needs and barriers to overcome. Technology can help identify the individual member’s social needs and social risk factors and create a strategy for helping members navigate through the next step, whether that’s arranging a ride to get to their appointment, helping them make a phone call or identifying barriers in their way.

This doesn’t just apply to how we address member needs. After all, personalized healthcare must go beyond the care received. It’s about meeting members where they are with the right message, at the right time, using the right communication method. Technologies as simple as SMS can enable care teams to blend the authentic with the automated to be both human and scalable.

Finding Unique Solutions

Similar to supporting a personalized engagement approach, leveraging technology that is smart enough to translate member information into actionable insights leads to better health outcomes. Insights from sophisticated data models (like who is housed in a safe, secure environment) can help determine a member’s next best action.

Technology can inform the depth and balance of intervention each member needs, allowing us to determine how much support an individual requires. Some members will need more support to navigate their situation and others will need less.

Knowing the individual need helps to build connections on a personal level, moving the clinical need aside to ensure relationships with members are built on trust. While ultimately the goal is to address the clinical need and improve health outcomes, relationship building is a critical first step that can’t be overlooked, and data models and strategic communication can identify where to go next.

Additional Resources

- A Better Way to Address Social Determinants of Health

- Closing the Health Equity Gap: Reducing Claims Costs By 40%

- The Distinction Between Health-Related Social Needs & Social Determinants of Health

- Health-Related Social Needs: Approaching Care From the Ground Up

- Technology as a Social Determinant of Health